Ladies Reading Room at Woodside Library with a fine display of headwear. The original libraries all provided separate space for the ladies at a safe distance from the gentlemen, who used the General Reading Rooms.

These images came from a photographic study of Glasgow's libraries in 1907. They were issued to commemorate Andrew Carnegie's visit to Glasgow on September 17th 1907. Carnegie came to the city to lay the memorial stone of the Mitchell Library and to address the Annual Conference of the Library Association.

The photographs were contributed to my 'Landmarks of

Literacy' exhibition by Wilma Moore, the librarian at Langside Library.

Bunnets were in style for the girls as well as the boys at the juvenile issue counter at Anderston Library in 1907!

Popular Children’s fiction of the time portrayed youngsters as the central characters in stories where the adult world was seen as a completely separate place. Books such as "Treasure Seekers" (1899), "Five Children and It" (1902) and "The Railway Children" (1906) were early examples of the genre which remained popular up until the 1960's.

Small boys under the strict supervision of the attendant at Kingston Library. Note the long list of "Daily Conduct Rules" attached to the wall to the left of the picture.

The libraries at the time would have had plenty of adventure stories for the younger readers. Edinburgh born Robert Louis Stevenson's "Treasure Island" had been published in 1883. Rudyard Kipling's "Jungle Book" appeared in 1895 & 1896 and his "Just-So Stories" in 1902. All these books would have been popular with young boys.

The adventures of "Tarzan of the Apes" were soon to follow from across the Atlantic, with 14 books in the series which began in 1912.

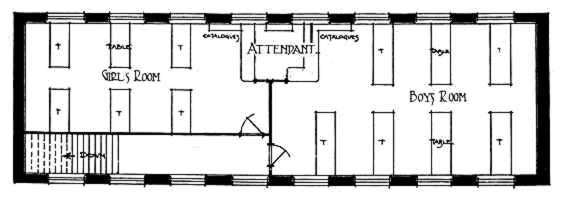

The wee girls had, of course, to have a separate reading room to protect them from the wee boys!

The plan view of the reading rooms shows the attendant in a central position which allowed him to supervise the children of both sexes while keeping them apart. The youngsters were allowed a glimpse of each other through the glass screen!

The old dictum that "children should be seen and not heard" was carried even further by the planners of Glasgow’s Carnegie libraries who endeavoured to make sure that the youngsters would be neither seen nor heard by the adult readers.

The plan view of Parkhead library (above) shows how the children's entrance to the right, is not even in the same street as the main entrance. There is no intercommunication at all between the children's area and the other public areas, ensuring that the adults were totally insulated from the disturbing influence of the wee ones.

Periodical rack in General Reading Room of Townhead Library. When it first opened the library held 39 weekly and 85 monthly and quarterly periodicals as well as 55 weekly/ daily newspapers.

Compulsory education created a huge newly literate public, many of whom sought merely to be amused and entertained by their reading, while others desired more to extend their education or pursue their hobbies and interests.

Issue counter at Parkhead Library, Glasgow in 1907, at a time before borrowers were trusted to select their own books from the shelves.

The shelves of the new libraries would hold many books familiar to readers of today, such as Robert Louis Stevenson's "Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hide" (1886) and Bram Stoker's "Dracula" (1897) which were early examples of the horror genre.

General Reading Room at Townhead Library, Glasgow. Notice the newspaper stands and the periodical racks in the distance

At the turn of the century there was an information revolution similar to the digital revolution which surrounds us at the start of the new Millennium.

On 18th September 1907, the day after he was presented with these photographs at the stone laying ceremony, the Glasgow Herald reported Carnegie's address to the annual conference of the Library Association where he had commented on the role of the librarian to "solace, refine and elevate the community".

To provide Carnegie with a contrasting opinion during his visit, the editor also published the following letter from a Mr Gardner of Carstairs who did not share the philanthropist’s views on the benefits of the new libraries.

The periodicals of the day reflected these different categories of readers. The staid traditional magazines such as "Blackwoods" or "Chambers Journal" were soon joined by newer lighter more entertaining periodicals. The "Strand" magazine, which was published from 1891 until 1950 was incredibly popular with its serialisation of cliff-hanging tales. Arthur Conan Doyle's famous detective Sherlock Holmes made a monthly appearance in the magazine.

A magazine article was allegedly behind Carnegie's idea to establish his Hero Fund following his retirement from business. The idea apparently came to him after he read a tale of heroism in the American "Century" magazine about a mine rescue in Pennsylvania.

Authors such as Jules Verne and H.G. Wells played an important part in spreading the modernistic ideas, which accompanied the new century.

Following translation of Verne's works originally published in French, Wells produced science fantasies such as "The Time Machine" (1895) and "War of the Worlds" (1898) to captivate readers' imaginations.

Many of the popular newspapers of today had their origins in this period.

The Daily Mail had been founded in 1896 at a cost of a halfpenny, and was soon followed by the Daily Express in 1900 and the Daily Mirror in 1903. On a more local level the Daily Record had been published in Glasgow since 1895, and the Evening Times since 1876, keeping the citizens up to date with all the latest gossip, news and sport.

The traditional solid journals such as the Glasgow Herald and the Scotsman were still very popular with large sections of the public. These newspapers provided their readers with a very wide view of the world, with up to the minute coverage of local, national and international events, as well as accounts of sporting events and social occasions.

The advent of the public library at that time allowed everyone access to all these newspapers as well as to books and periodicals.

Not everyone saw the benefit of allowing the working classes to have free use of books and newspapers. Critics suggested that the new libraries would be just providing space for idlers to waste their time in pursuits such as selecting horses from the racing pages. Some concerned librarians took preventative measures by removing the offending pages from the newspapers!

Mr Gardner includes the abbreviation "NB" for "North Britain" in his home address. This usage was a reaction to the perceived threat of Home Rule in Ireland which led some people at the time to deny their Scottish nationality, seeing themselves as purely " North British".

Carnegie had publicly supported the Home Rule cause and had been an avowed anti-monarchist since his youth. He had even bought newspaper interests in England in the 1880's to promote his radical views.